There are thousands of ways of exploring this relationship, through philosophy as well as history. I was inspired by my photography lecturer Nicola Read to think about the way the development of technical apparatuses for seeing were integrally related to the quest for three dimensional representation in art, and how these developed in the early nineteenth century.

The creation of images is usually thought of as the product of human skill combined with available technologies. But these elements alone do not create images. Every element of image-production is highly culturally variable and depends on the world-view of that society at its given historical moment. Even the concept of art and the image is not universal: in Australian indigenous languages there are no words for either.

The value of art in the Western tradition, at least since the Ancient Greeks and Romans, was determined by the extent to which art could faithfully mimic or recreate reality. Sculpture aimed at producing images of subjects, human or otherwise, as virtual duplicates, but only of the beautiful. Sculpting the human or animal form was a kind of homage to a spiritual or Godlike source. In the Ancient World, the Gods were ever-present and the human form was taken to represent them, for instance in illustrating mythologies.

Laocoon and his Sons, early Hellenistic period (Greece) c 300 BCE

Laocoon and his Sons, early Hellenistic period (Greece) c 300 BCE

Painting in early Western society (medieval period) was also seen as a spiritual act. The most popular subjects for representation were religious ones expressed in many different kinds of materials and styles but always idealized, imagined as Holy Beings in a perfect world. These paintings did not try to mimic the real but depicted the transcendent, especially images of Mary, Jesus and the saints. They were depicted in flattened non-perspectival forms as if floating in an indeterminate space. Since there are no images of the actual Mary or Jesus, artists were able to project conventional ideas. In the painting below, Jesus looks exactly like a little man with a neat haircut.

Source: http://sofieo.iics-k12.com/files/2014/06/a00009b9.jpeg

It was not until the Renaissance that the task of art moved towards mimesis, that is, accurate representation of an actual external world. It was with the idea of producing the most accurate images of reality that the first camera-like machine emerged, guided by the upsurge of interest in optics during the 14th and 15th centuries. The first use of a mechanism of reproduction was developed in order to assist the creation of traditional art, in particular of drawing and oil painting.

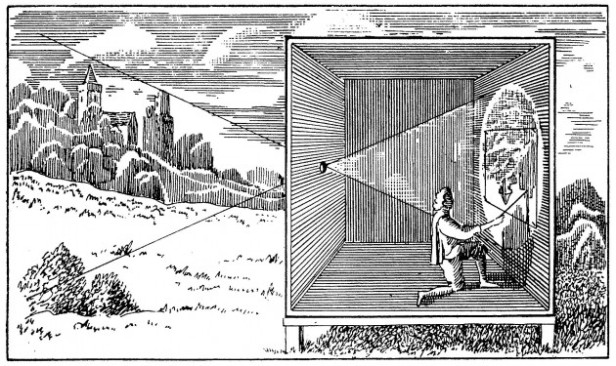

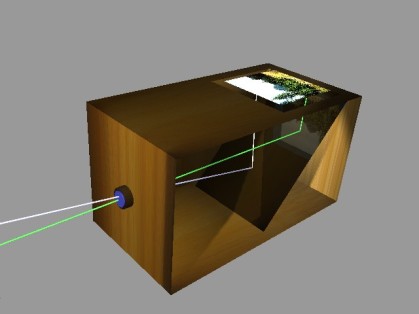

The first mechanism identified with certainty is the Camera obscura. This is essentially like a photographic camera without any light-sensitive film or plate. It allowed the accurate reproduction of perspective. The use of perspective, the creation of a three dimensional image onto a two dimensional medium, was considered the highest achievement in art. Artists labored for years learning the difficult techniques involved in classical painting. The Camera obscura however made it possible to trace accurate images of the real world onto a support – canvas, wall, wood – without the former highly complex techniques learnt through years of apprenticeship.

Camera obscura effects took place unintentionally. The image of Prague Castle projected onto a wall below is an example of the kind of natural accident which led scientists to work on developing deliberate camera obscura techniques.

The Camera obscura was a dark chamber or room with a hole in one wall, or at least a large box. The outside world was projected onto the opposite wall. Deliberate structures were created to permit artists to view and trace out the world outside. Note that Camera obscura images are always upside down. This demands a kind of faith in the outline and shading of what is being observed since the artist’s mind cannot be sure exactly what he is seeing.Over time various boxes utilizing the same principle were developed, and began to look more like cameras.

Camera Obscura box

VERMEER AND THE CAMERA OBSCURA DEBATE

There have been many recent controversies over the extent to which Camera obscura techniques were applied by traditional artists in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Probably the most famous case is that of Vermeer.

Officer and Laughing Girl

Johannes Vermeer. 1655-1660

Oil on canvas, 50.5 x 46 cm.

Frick Collection, New York

Certain elements seen in Vermeer’s paintings are seldom found in the work of other artists of the period. It is believed he used the Camera obscura, although there is no record of this at the time. The first to propose this was Joseph Pennell, an American lithographer and etcher, who noted the discrepancy in scale of the two figures in Vermeer’s painting Officer and Laughing Girl (1655-1660). Even though the officer is seated close to the girl, he appears disproportionately large. His head is about twice as wide as that of the girl. Eyes accustomed to modern photography are comfortable with foreground objects appearing very large in snapshots but it was almost unheard of in 16th century painting.

Other elements include colour and tonality in Vermeer’s paintings which seem to be blended perfectly, with highlights on foreground objects which break up into dots. In Delft, where Vermeer lived, Anthony van Leeuwenhoek was a famous grinder and user of lenses, and was the executor of Vermeer’s estate. Many art historians have entered the debate about whether or not Vermeer’s paintings were constructed using the Camera obscura, and it is interesting to see the way the visual qualities produced by the Camera obscura image as against the naked eye make sense with his paintings.

See the account on the Vermeer 2.0 website for a full discussion.

http://www.essentialvermeer.com/camera_obscura/co_one.html#.V8zKj5N973AT

his suggests that when we viewers, accustomed to seeing images in photographs, look at Vermeer’s paintings we are entirely ready to “read” them, although viewers in his own time may have found them very strange.

The Camera obscura opened up a way for an artist to paint or draw a scene from the real world. Until then, most paintings were about subjects created from imagination or mythological stories. From the sixteenth century on, such paintings continued to be created, but the use of the Camera obscura allowed a different approach to perspective and composition. Even grand history paintings of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries could use Camera obscura techniques to construct elements of the image separately.

Watson and the Shark. John Singleton Copley, 1778. Oil on canvas.

Watson and the Shark. John Singleton Copley, 1778. Oil on canvas.

I don’t know if any element of this painting really used Camera obscura techniques but the drawing outlines of the individual figures are realistically constructed with accurate perspective. The shark on the other had looks like a plastic model.

DAGUEARROTYPE AND THE CHEMICAL CONNECTION

Being able to project a three dimensional image onto a flat surface so it could be traced or painted in moved art one step closer to photography. The development of lenses and understanding of optics advanced rapidly. However it was the conjunction of optical techniques with advances in chemistry that really made modern-style photography possible. There were several intermediate steps involved, each of them relying on greater understandings of chemistry.

In 1727 Johann Heinrich Schulze, Professor of anatomy in Vienna, proved that the darkening of silver salts was caused by light and not heat. He used sunlight to record words on the salts but could not preserve the images permanently. In 1826 a Camera obscura was fitted with a pewter lens, producing the first successful photograph from nature. It required 8 hours exposure. The problem was to find a way of securing the image from the camera onto a surface other than by painting or drawing it.

The first solution to the problem was the Daguerrotype, named after Frenchman M. Daguerre, a professional scene painter for the Paris theatre. From 1822 – 1839 he was co-proprietor of the Diorama in Paris, an auditorium displaying immense scenes of famous places and historical events. The scenes were painted on tranlsucent paper or muslin and by using changing lighting effects he was able to present very realistic tableaux. The amazing trompe l’oeil effects were heightened by music and by positioning of real objects animals and people in front of he painted scenery. The Diorama introduced the display of real objects combined with images and in a way was the precedent for the movies.

Diorama, Port du Boulogne

However Daguerre wanted to go further and find a way of recording permanently the images he created. Somehow he put together a Camera obscura style box with a plate inside it on which light would leave an accurate impressionThe first images were of objects, that is, still life pictures. The earliest reliable dated daguerrotype is the still life with plaster casts which appears at the top of this post.

For a decade or so, these were the kind of images being produced. It was not possible to include things that moved. People would ruin the picture. But the shorter the exposure required, the more it was possible to include the human image. The earliest known Daguerrotype showing people was taken by Daguerre one spring morning in 1838 from the upstairs window of the Diorama. It is an image of people at the corner of the Boulevarde du Temple in Paris. It showed amazing detail and fascinating perspective angles, which would have been almost impossible in classical oil painting – even to “see” that kind of image would have been too strange to artists of that period.

Daguerre’s image of the streetscape outside his window along the Boulevarde du Temple. Note the two figures to the lower left of the image

Daguerre’s image of the streetscape outside his window along the Boulevarde du Temple. Note the two figures to the lower left of the image

The Daguerrotype Studio

As the technical elements involved in producing a stable image evolved, the idea of having one’s image professionally created arose. This was obviously a far more simple and faster method than sitting for an oil painting portrait, which had been the main method of being recorded for posterity prior to that time. Studios were opened in various cities where the Dageurrotype image became a popular way of recording important people.

An illustration of Richard Beard’s Daguerrotype studio, from a woodcut by George Cruikshank, 1842.

http://www.photohistory-sussex.co.uk/studio1841%20label.jpg

The detailed techniques involved in the creation of the Dageurrotype are here:

http://www.dagazine.com/mi/exhibit/brochure.htmfor a more complete description of the process.

PHOTOGAPHY AS THE REPLACEMENT OF CLASSICAL FORMS OF ARTRevolution of Technique c 1840-1900

The dageurrotype was able to record accurate detail. Naturally it was compared with painting and drawing as the dominant method of picture making.

Early processes could not produce the range of colours and tones in classical art. But it was immediately obvious that this technique of reproducing the real, with as much fidelity as possible, by a technical apparatus challenged fundamentally the role of art. Learning to draw and mastering the laws of linear perspective and chiaroscuro were at one blow rendered irrelevant for image production Academic painter Paul Delaroche declared “From today painting is dead”. Many artists feared that “with this technique, without any knowledge of chemistry or physics, one willbe able to make in a few minutes the most detailed views”.

Section 3 of the Hemicycle 1841-1842

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/52/Paul_Delaroche_-_H%C3%A9micycle.jpg

Section 2 of the Hemicycle.

The innumerable hours of painstaking and detailed work involved in major art works of the era could be cut short to a single scene constructed like what we would know as a film set. The lack of colour however remained a major difference.

The technique of daguerreotype spread quickly in conjunction with tourism development especially views of famous monuments in Egypt, Israel, Greece and Spain. Better communications in Europe, especially the development of the railway systems, encouraged people to travel far from home. They wanted to bring back mementos of their travels. The Daguerrotype images made it easy for engravings to be made from them. One of the first books of views made from engravings based on Dageurrotype images was published as Excursions dageuerriennes 1841-1843. Still, they depended on very long exposures, as long as an hour, so moving objects could not be recorded and portraiture was not practical.

The Great Acropolis, Daguerrotype 1850.

Experiments began in Europe and US to improve the optical chemical and practical aspects of the process to suit portraiture. The first known photography studio opened in NYC in 1840. Alexander Wolcott opened a “parlour” for tiny portraits, using a macera with a mirror instead of a lens. Voigtlander reduced Daguerre’s clumsy wooden box to smaller proportions so travellers could carry them. Meantime in 1841 another Viennese Franz Kratochwila published a chemical acceleration process where combined vapours of chlorine and bromine increased the sensitivity of the plate by five times. Tiny portraits could be produced while exposure times were reduced to 1-3 minutes.

Soon however it became possible to produce much larger and more lasting portraits. Note everyone was convinced that this was a good thing, especially in America, where photographic type portraiture was at first suspected of being immoral.

Daguerreotypes were popularly and primarily used for portraits. Unlike most photographs today, in which images are printed from transparent negatives onto paper, the daguerreotype was a polished copper plate upon which an image was directly exposed. No negative used in the process and so each daguerreotype was a unique, one-of-a-kind object. With its brilliant, mirror-like surface and its ornate case, small enough to hold in the hand or carry in the pocket, the daguerreotype was suited to a vivid and intimate representation of a loved one.

Despite its value as a means of memorializing friends and family, photography did not have an immediate market. In fact, it was photography’s almost magical ability to reproduce life that elicited fear and suspicion from many people. In an effort to assuage anxieties about the medium and to gain public credibility, photographers sought to take and to display portraits of America’s elite. In an age when phrenologists offered to read a person’s character based on their physical characteristics, portraits of society’s leaders were thought to have an edifying and moralizing influence on the viewer. Portraits of esteemed personages such asLyman Beecher, Cornelius Vanderbilt, Dolley Madison, and Abraham Lincoln drew the public to the photographers’ studios and provided the genesis for a cult of celebrity that would grow with the evolution of photography.

CONCLUSION:

The early history of modern technologies of the image was bound up with a Western interest in the production of images and their social circulation. This changed from a mainly religious interest to become more and more relevant to the development of modernity itself. Travel, individuality, the desire for status and achievement and the wish to record one’s own image emerged alongside the rapid scientific changes in optics and chemistry.

While the camera obscura and the dageurrotype were both dead ends as technical inventions in themselves, they were essential to instigating the change in world view and perspectives on the image which accompanied modernity as a philosophical and social movement. The idea of mechanical reproduction was there long before the development of the techniques was possible. Modern photography emerged from this basis, and most of its main significances (before digital photography) had already been pioneered by early to mid-nineteenth century experiments in image-creation.

We now “see” with photographic eyes. That is, although our eyes are the same as our ancestors’ in their physiological construction, the way we experience images has been imprinted on our cognitive processes through the development of photography. This becomes especially significant when a would-be artist tries to draw or paint from life. Open-air or even painting in the studio constantly makes us tempted to revert to a photographic image. It is commonplace now for artists to take a photograph of their subject and work entirely from that. This produces something very different from the image which emerges through unmediated sight. The impressionists tried to capture this and rarely or never used photographs. Bonnard is another example, especially his interiors, which it would be impossible to produce if working from a photograph. It used to be said that Art was dead because of photography. Usually people think that is because the photograph creates an absolutely accurate image with all the detail included. But really the photographic apparatus itself creates its own vision which is no “truer” than that of the unmediated human eye. It is the freedom from photographic vision which makes abstract art so compelling. Abstraction produces images which cannot be seen through the photographic imagination. I think Gerhard Richter turned to abstraction to resolve this issue. But that is a topic for another day.

Very informative!

LikeLike